Coelacanth

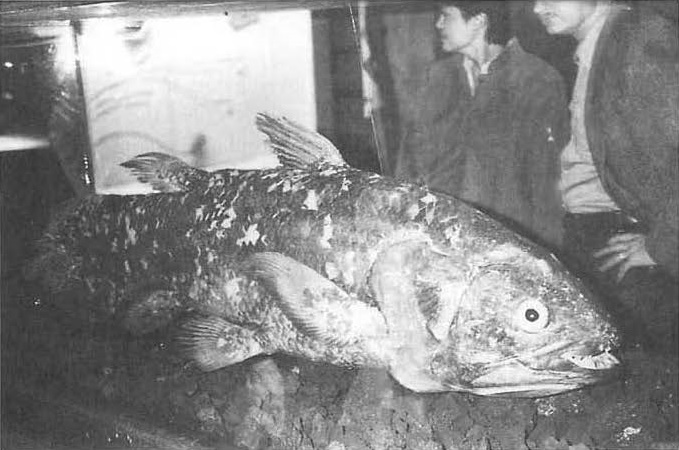

A few coelacanths are displayed in natural history museums around the world, like this one in Chicago’s Field Museum. (Loren Coleman)

The coelacanth (Latimeria chalumnae) is the darling of cryptozoology. Its story demonstrates that unknown, undiscovered, or at least long-thought-extinct animals can still be found.

The coelacanth, a lobe-finned fish, first appeared during the Devonian period, some 350 million years ago. Its body varies from bright blue to brownish in colour and produces large amounts of oil and slime. Fossils found in many parts of the world indicate that during the coelacanth’s long history, various types inhabited lakes, swamps, inland seas, and oceans. Before 1938 paleontologists thought that the coelacanth had become extinct about 65 million years ago, when the dinosaurs disappeared.

The first “modern” coelacanth was a five-foot-long, 127-pound, large-scaled blue fish brought up in a net off South Africa by Captain Hendrick Goosen, of the trawler Nerine, who was fishing the coastal waters of the Indian Ocean, near Cape Town, South Africa. On December 23, 1938, Goosen took his catch to a local fish market, and called Marjorie Courtenay-Latimer, curator and taxidermist at the East London Museum, northeast of Cape Town, to examine his haul, as she often did, looking for any unusual specimens for her collection. Courtenay-Latimer wished the crew a happy holiday and was about to leave when she saw a blue fin, and she revealed from under a pile “the most beautiful fish I had ever seen, five feet long, and a pale mauve blue with iridescent silver markings.” She talked a taxi driver into taking the smelly fish back with her to the museum, and there identified it as a coelacanth, later confirming her find with the leading South African ichthyologist Professor J. L. B. Smith of Rhodes University, Grahamstown, some fifty miles south of East London. Meanwhile, Courtenay-Latimer’s museum director in East London was less impressed with the find. He rejected the fish as a common grouper. Smith, who was on Christmas holiday, was not able to confirm it was a coelacanth until after a taxidermist had thrown away all of the important internal organs to mount what would turn out to be the “catch of the century.”

But the story of the coelacanth’s “discovery” does not end there. With no internal organs left from the East London specimen, many questions remained unanswered. Smith was obsessed with finding a second intact specimen. Finally, on December 21, 1952, fourteen years after the discovery of the first living coelacanth, lightning would strike again while Smith was on another Christmas holiday. Captain Eric Hunt, a relocated British fisherman who had attended one of Smith’s coelacanth lectures and had also become obsessed with locating another coelacanth, was returning to the port of Mutsamudu on the Comoros island of Anjouan, off the coast of Mozambique, when he was approached by Ahamadi Abdallah, a Comorian who was carrying a hefty bundle. Abdallah had pulled in by hand what the locals called a gombessa, a large fish that turned up on the Comorian lines now and then. The second coelacanth had finally been found.

Years later, ichthyologists were shocked to learn that the local islanders had been catching and eating these “living fossils” for generations. Since then more than two hundred individual fish from the Comoros have been caught and studied. Most natural history museums have a mounted specimen on exhibit. Up-to-date news on this now endangered fish species can be found at coelacanth researcher Jerome F. Hamlin’s website: http://www.dinofish.com

Four years after the “discovery” of the second coelacanth, Hunt disappeared at sea after his schooner ran aground on the reefs of the Geyser Bank between the Comoros and Madagascar. He was never found. Smith wrote his account of the coelacanth story in the now classic Old Fourlegs, first published in 1956. Smith died in 1968. Captain Hendrick Goosen passed away in 1988, just after the fiftieth anniversary of the “discovery” of the coelacanth. And Marjorie Courtenay-Latimer was alive and well and still living in East London as of 1998, the lone survivor of the coelacanth story.

Intriguingly, this fossil fish is back in the news with a “second” rediscovery in Indonesia, by marine biologist Mark Erdmann and his wife, Arnaz Mehta, a nature guide, in 1997-98 (see Indonesian coelacanths). French coelacanth chronicler Michel Raynal, who had predicted that the fish would be found in Indonesian waters, thinks more discoveries of the fish in unexpected locales will occur in the future. He writes that “there is a tantalizing possibility that an unknown coelacanth is lurking off the coasts of Australia.” There are also reports of other coelacanth populations from around the world, reportedly as far away from the Comoros as the Gulf of Mexico.

SOURCE:

The Encyclopedia of Loch Monsters,Sasquatch, Chupacabras, and Other Authentic Mysteries of Nature

Written by Loren Coleman and Jerome Clark – Copyright 1999 Loren Coleman and Jerome Clark