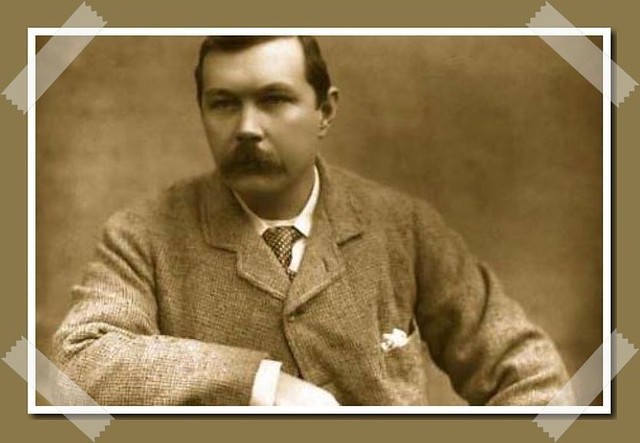

Doyle, Sir Arthur Conan

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1858–1930) Remembered more for his brilliant detective character Sherlock Holmes, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was an ardent spiritualist who tirelessly defended Spiritualism and the legitimacy of Mediums. Unlike Holmes, who was shrewd and skeptical, Doyle believed in virtually anyone or anything that claimed to give evidence of survival or life on the Other Side.

Born in 1858, Doyle grew up in the sunshine of the British Empire. He was sublimely self-confi dent about the rightness of things—white, English, upper class— and his ability to influence events. He was tall; he was opinionated; and he was a successful physician. He loved England, his home and family, and the ordered beauty of life under the reigns of Victoria and Edward. Doyle also was a gifted storyteller.

His first exposure to the paranormal came while he was a physician at Southsea in 1885–88. Doyle participated in Table-Tilting Séances at the home of his patient General Drayson, a mathematician, and was intrigued but unconvinced. The subject piqued his interest enough, however, to lead Doyle into further study and membership in the Society for Psychical Research (SPR).

After 30 years of study, Doyle wholeheartedly em braced the faith of Spiritualism in 1916. His second wife, Jean, lost her brother Malcolm at the World War I battle of Mons that year, and soon thereafter she began Automatic Writing. The Doyles felt their mission so strongly that they began lecturing on spiritualism; thousands of bereaved trying to contact fathers, sons and brothers lost in World War I only helped their cause. In 1918 Doyle’s eldest son, Kingsley, fell at the battle of the Somme. Doyle was bereaved but sincerely believed Kingsley lived in the beyond. He reported that Kingsley communicated with him and encouraged his spiritual work.

Doyle’s lectures, first in Great Britain and then in Australia and New Zealand, followed the publication of his books The New Revelation (1918) and The Vital Message (1919). For the next 12 years the Doyles traveled ceaselessly, lecturing in America, South Africa, England and northern Europe. He drew large crowds eager to see the famous novelist and find some comfort in his words. And Doyle never failed to entertain as well as instruct. His love for detail sketched a picture of the Other Side as happy, well-ordered and busy, rather like Sussex. Doyle claimed to be uninterested in physical phenomena, but he actively supported manifestations obtained through Spirit Photography and the search for proof of Fairies. In the early 1920s, Doyle was publicly embarrassed by being taken in by badly faked photographs of the Cottingley Fairies.

In 1922, Doyle and his friend Harry Houdini argued over a Séance. Houdini had met the Doyle family after a performance at the Hippodrome in Brighton, England, in 1920, and the two families had struck up a friendship. When the Doyles toured America that year, they asked Houdini and his wife Bess to join them in Atlantic City for a short vacation. While there, Doyle told Houdini that his wife Jean, who wrote automatically, felt she could get the magician in touch with his beloved mother, a feat he desperately wanted.

The only sitters in addition to Houdini were Doyle and his wife. Lady Doyle soon was seized with the spirit and began writing furiously. The manuscript was full of messages to “her boy,” thanking the Doyles for their intercession and telling Houdini of her love and desire to be with him. Houdini, always the skeptic but wanting to believe, was moved but unconvinced.

He had good reasons for his skepticism. Lady Doyle had started the manuscript with a cross at the top of the page, and Mrs. Weiss (Houdini’s real name) was Jewish. The writing was in good English, and Houdini’s Hungarian mother spoke broken English. And, most telling to Houdini, the Séance was held on his mother’s birthday, June 17, and she never mentioned it. Houdini denied that he had received true communication, and the Doyles never forgave him. The friendship broke under the strain.

By 1924, Doyle and Houdini angrily opposed each other on the question of Mina Stinson Crandon’s mediumship. Crandon, alias Margery, was investigated by a committee of the Scientific American to verify the truth of her talents. As a member of the committee, Houdini was outraged that the rest of the group had examined Margery without him and were ready to endorse her. He proposed a series of tests to find her fraudulent but ended up chastised for his ungentlemanly behavior. Doyle called him a bounder and cad and supported Margery without question. Complicating the situation was Doyle’s conviction that Houdini, an acknowledged medium-baiter, was himself the world’s greatest medium, unable to perform many of his escape stunts without dematerializing his body and then rematerializing. (See Materialization.)

Fans of the logical Sherlock Holmes have asked how his creator could be so credulous. Part of the problem was Doyle’s supreme self-confi dence, and part was his need to believe regardless of the evidence. As time went on, Doyle regarded himself as the messiah of spiritualism and prophet of the world’s future; indeed, he was nicknamed the movement’s St. Paul. Consequently, anyone suggesting he might be mistaken was regarded as an ignorant fool.

Not long after Lady Doyle began Automatic Writing, she heard from an Arabian spirit control named Pheneas, who warned against the evil nature of the world. In 1923, Pheneas told the Doyles the world was sinking fast into a slough of evil and materialism, and that God must intercede to save it. To that end, Pheneas said a team of spiritual scientists were at work connecting vibrating lines of seismic power that would trigger earthquakes and tidal waves, signaling Armageddon. Doyle’s task was to prepare people’s minds for the revelation.

By 1925, Pheneas was outlining the specifics of the upheaval. Central Europe would be engulfed by earthquakes and storms, followed by a great celestial light. Russia would be destroyed, Africa flooded and Brazil razed by some sort of eruption. America would suffer another civil war. And the Vatican, described as a sink of iniquity, would be swept away. England would be the world’s beacon (ideas similar to those of Empire), flashing especially strong from the power station of cosmic energy surrounding the Doyle home. Christ would appear there before making plans for the Second Coming.

Doyle kept a notebook of prophesied events, noting that he would pass over with his entire family after the conflagration. But 1925 passed with no extraordinary upheaval. Shortly before his death, Doyle began to wonder if he and his family had been the butt of a great joke on humans by members of the Other Side, since none of Pheneas’s predictions had come about.

Doyle died on July 7, 1930. On July 13th, his family and friends held a reception at the Albert Hall in London, leaving an empty chair for the old fighter. Medium Estelle Roberts claimed she could see him and passed on a message the family felt was evidential. Others have also claimed communications; the most noteworthy was received by Eileen J. Garrett that same year.

FURTHER READING:

- Brandon, Ruth. The Spiritualists. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1983.

- Doyle, Sir Arthur Conan. The Coming of the Fairies. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1922.

———. The Edge of the Unknown. New York: Berkley Medallion Books, 1968. First published by G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1930. - Fodor, Nandor. An Encyclopaedia of Psychic Science. Secaucus, N.J.: The Citadel Press, 1966. First published 1933.

- Higham, Charles. The Adventures of Conan Doyle: The Life of the Creator of Sherlock Holmes. New York: W. W. Norton & Co., Inc., 1976.

- Houdini, Harry. Houdini: A Magician Among the Spirits. New York: Arno Press, 1972.

SOURCE:

The Encyclopedia of Ghosts and Spirits– Written by Rosemary Ellen Guiley – September 1, 2007