Salem witchcraft hysteria

Trials and executions of accused witches in Salem, Massachusetts, from 1692 to 1693. In all, 141 people were arrested as suspects, 19 were hanged, and one was pressed to death. The principal accusers were girls who claimed that witches in league with the Devil were attacking them and sending their Demon Familiars to attack them. Adding to the hysteria were widespread Puritan fears of Demonic influences in New England, as well as political and social tensions. Tensions were already high between Salem Village and Salem Town when the witch panic erupted, starting in the home of the Reverend Samuel Parris, who had arrived to be the fourth minister in Salem Village in 1689. Before becoming a minister, Parris had worked as a merchant in Barbados; when he returned to Massachusetts, he took back a slave couple, John and Tituba Indian (Indian was probably not the couple’s surname but really a description of their race). Tituba cared for Parris’ nine-year-old daughter, Elizabeth, called Betty, and his 11-year-old niece, Abigail Williams. Tituba probably regaled the girls with stories about her native Barbados, including magic, divination, and spell-casting.

The girls were joined by other young girls in Salem Village—Susannah Sheldon, Elizabeth Booth, Elizabeth Hubbard, Mary Warren, Sarah Churchill, Mercy Lewis, and Ann Putnam, Jr. (Ann Putnam, Sr., was her mother). Dabbling in the occult was fun in the beginning, but it soon frightened them to the point of having fits. In January 1692, Betty Parris and others began having fits, crawling into holes, making strange noises, and contorting their bodies. It is impossible to know whether the girls feigned witchcraft to hide their involvement in Tituba’s magic, or whether they believed they were possessed. In the climate of the times, they were declared by experts to be bewitched.

Seventeenth-century Puritans believed in witchcraft as a cause of illness and death and thought that witches derived their power from the Devil. So, the next step was to find the witch or witches responsible, exterminate them, and cure the girls. After much prayer and exhortation, the frightened girls, unable or unwilling to admit their own complicity, began to name names. Tituba made a witch cake out of rye meal mixed with the urine of the afflicted girls. Taken from a traditional English recipe, the cake was then fed to the dog. If the girls were bewitched, one of two things should happen: Either the dog would suffer torments, too, or he would identify the witch as her familiar. The Reverend Parris furiously accused Mary Sibley of “going to the Devil for help against the Devil,” lectured her on her sins, and publicly humiliated her in church. But the damage had been done: “The Devil hath been raised among us, and his rage is vehement and terrible,” said Parris, “and when he shall be silenced, the Lord only knows.”

The first accused, or “cried out against,” were Tituba herself, Sarah Good, and Sarah Osborne. Warrants for their arrest were issued, and all three appeared before Salem Town magistrates John Hathorne and Jonathan Corwin on March 1. The girls, present at all interrogations, fell into fits and convulsions as each woman stood up for questioning, claiming that the woman’s specter was roaming the room, biting them, pinching them, and often appearing as a bird or other animal someplace in the room, usually on a particular beam of the ceiling. Hathorne and Corwin angrily demanded why the women were tormenting the girls, but both Sarahs denied any wrongdoing.

Tituba, however, beaten since the witch cake episode by Parris and afraid to reveal the winter story sessions and conjurings, confessed to being a witch. She said that a black dog—a favoured form of the Devil—had threatened her and ordered her to hurt the girls, and that two large cats, one black and one red, had made her serve them. She claimed that she had ridden through the air on a pole to “witch meetings” (see Sabbat) with Good and Osborne, accompanied by the other women’s familiars: a yellow bird for Good, a winged creature with a woman’s head, and another hairy one with a long nose for Osborne. Tituba cried that Good and Osborne had forced her to attack Ann Putnam, Jr., with a knife just the night before, and Ann corroborated her statement by claiming that the witches had menaced her with a knife and tried to cut off her head.

Tituba revealed that there was a coven of witches in Massachusetts, about six in number, led by a tall, whitehaired man dressed all in black, and that she had seen him. During the next day’s questioning, Tituba claimed that the tall man had approached her many times, forcing her to sign his devil’s book in Blood, and that she had seen nine names already there.

All three women were taken to prison in Boston, where Good and Osborne were locked in heavy iron chains to prevent their specters from traveling about and tormenting the girls. Osborne, already frail, died there. Tituba joined the ranks of the accusers.

Complicating the legal process of arrest and trial was the loss of Massachusetts Bay’s colonial charter. The colony was established as a Puritan colony in 1629 with selfrule, the English courts revoked the charter in 1684–85, restricting the colony’s independence. Massachusetts Bay had had no authority to try capital cases, and for the first six months of the witch hunt, suspects merely languished in prison, usually in irons.

The loss of Massachusetts’ charter represented to the Puritans a punishment from God: The colony had been established in covenant with God, and prayer and fasting and good lives would keep up Massachusetts’ end of the covenant and protect the colony from harm. Increasingly, the petty transgressions and factionalism of the colonists were viewed as sins against the covenant, and an outbreak of witchcraft seemed the ultimate retribution for the colony’s evil ways. Published sermons by Cotton Mather and his father, Increase Mather, and the long-winded railings against witchcraft from the Reverend Parris’ pulpit every Sunday convinced the villagers that evil walked among them and must be rooted out at all cost. In May 1692, the new royal governor, Sir William Phips, established a Court of Oyer and Terminer (“to hear and determine”) to try the witches. By May’s end, approximately 100 people sat in prison on the basis of the girls’ accusations. Bridget Bishop was first to be found guilty and was hanged on June 10.

The court had to deal with the issue of spectral evidence. The problem was not whether the girls saw the specters, but whether a righteous God could allow the Devil to afflict the girls in the shape of an innocent person. If the Devil could not assume an innocent’s shape, the spectral evidence was invaluable against the accused. If he could, how else were the magistrates to tell who was guilty? The court asked for clerical opinions, and on June 15 the ministers, led by Increase and Cotton Mather, cautioned the judges against placing too much emphasis on spectral evidence alone. Other tests, such as “falling at the sight,” in which victims collapse at a look from the witch, or the touch test, in which victims are relieved of their torments by touching the witch, were considered more reliable. Nevertheless, the ministers pushed for vigorous prosecution, and the court ruled in favour of allowing spectral evidence.

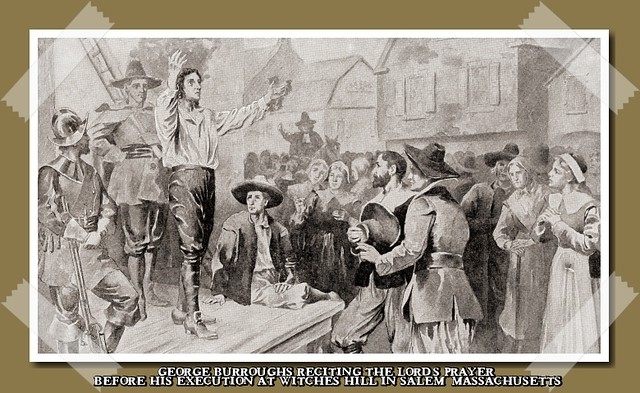

Of the executions, that of George Burroughs, formerly minister of Salem Village, stood out. Burroughs and several others were sent to be hanged at Gallows Hill on August 19. Before Burroughs died, he shocked the crowd by reciting the Lord’s Prayer perfectly, creating an uproar. Demands for Burroughs’ freedom were countered by the afflicted girls, who cried out that “the Black Man” had prompted Burroughs through his recital of the prayer. It was generally believed that even the Devil could not recite the Lord’s Prayer, and the crowd’s mood grew darker. A riot was thwarted by Cotton Mather, who told the crowd that Burroughs was not an ordained minister, and the Devil was known to change himself often into an angel of light if there were profit in doing so. When the crowd was calmed, Mather urged that the executions proceed, and they did. As before, the bodies were dumped into the shallow grave, leaving Burroughs’ hand and chin exposed.

Samuel Wardwell, completely intimidated, confessed to signing the Devil’s book for a black man who promised him riches. He later retracted his confession, but the court believed his earlier testimony. Wardwell choked on smoke from the hangman’s pipe during his execution, and the hysterical girls claimed it was the Devil preventing him from finally confessing.

Giles Corey, a wealthy landowner, was pressed to death September 19 for refusing to acknowledge the court’s right to try him. He was taken to a Salem field, staked to the ground, and covered with a large wooden plank. Stones were piled on the plank one at a time, until the weight was so great his tongue was forced out of his mouth. Sheriff George Corwin used his cane to poke it back into Corey’s mouth. Corey’s only response to the questions put to him was to ask for more weight. More stones were piled atop him, until finally he was crushed lifeless. Ann Putnam, Jr., saw his execution as divine justice, for she claimed that when Corey had signed on with the Devil, he had been promised never to die by hanging.

The hysteria subsided when the girls began accusing more and more prominent people, including the wife of the governor, Lady Phips. On October 29, Governor Phips dissolved the Court of Oyer and Terminer, and spectral evidence became inadmissible. The trials came to an end.

Eventually, the prosecutions were seen as one more trial of God’s covenant with New England—a terrible sin to be expiated. Those who had participated in the proceedings— Cotton and Increase Mather, the other clergy, the magistrates, even the accusers—suffered illness and personal setbacks in the years after the hysteria. Samuel Parris was forced to leave his ministry in Salem. By 1703, the Massachusetts colonial legislature began granting retroactive amnesties to the convicted and executed. Even more amazing, they authorized financial restitution to the victims and their families. In 1711, Massachusetts Bay became one of the first governments ever voluntarily to compensate persons victimized by its own mistakes.

In 1693, Increase Mather acknowledged in his Cases of Conscience Concerning Evil Spirits Personating Men that finding a witch was probably impossible, because the determination rested on the assumption that God had set humanly recognizable limits on Satan, but Satan and God are beyond human comprehension.

In 1957, the legislature of Massachusetts passed a resolution exonerating some of the victims. Still, citizens felt they should do more. In 1992, a memorial was erected to all the victims of the 1692 trial. It was dedicated by Elie Weisel, a Nobel laureate known for his work concerning the victims of Nazi concentration camps. The memorial is located at the Old Burying Point in Salem and is a parklike square with stone benches engraved with the names of the victims.

SOURCE:

The Encyclopedia of Demons and Demonology – Written by Rosemary Ellen Guiley – Copyright © 2009 by Visionary Living, Inc.

LIST OF VICTIMS :