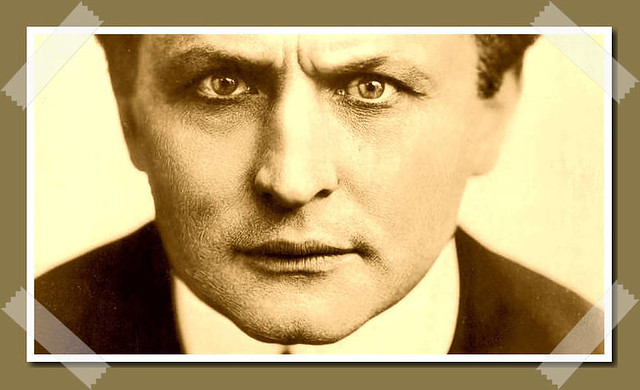

Harry Houdini

Houdini, Harry (1874–1926) A master illusionist and escape artist, Harry Houdini was perhaps the greatest stage magician of all time. He also spent most of his adult life trying to expose fraudulent spiritualist Mediums as nothing more than conjurers like himself. At the same time, he desperately sought someone who could convince him of the truth of Spiritualism and enable him to contact his dead mother.

Houdini was born Ehrich Weiss in Appleton, Wisconsin, on April 6, 1874, to Dr. Mayer Samuel Weiss, a rabbi, and his wife Cecilia. The Weisses were from Hungary. Even as a baby, his mother worried about Ehrich because he slept so little, often lying in his crib staring keen-eyed at the walls and ceiling. He learned to pick locks early on to steal jam tarts. By age six he was conjuring, making a dried pea appear in any of three cups. He was quite agile and athletic.

When a circus came to town, young Ehrich astonished the manager with his rope tricks. He performed during the circus’s stay, but his father refused to let him travel with the circus. He worked with a local locksmith at age 11 and could pick any lock submitted to him. Ehrich also worked odd jobs as a newspaper seller, bootblack and necktie cutter.

His goal was to be a stage magician, however. A book by the famous French magician Jean Robert-Houdin provided Ehrich with some conjuring tricks and secret codes for sleight-of-hand, and he worked up his first professional act with a friend named Hayman. They called themselves the Houdini Brothers, adding an “i” to the French magician’s name. When they parted later, Ehrich’s real brother Theodore joined the act. The boys appeared in dime museums and sideshows, escaping from packing cases and handcuffs.

In 1893, Houdini performed at a girls’ school and accidently spilled acid on a young girl’s dress. Mrs. Weiss made the girl, Beatrice (Bess) Rahner, a new dress, and Houdini delivered it to her home. Not long after, she and Houdini were married. Bess, who had been strictly brought up, at first thought Houdini was the devil disguised as a handsome man, but she soon came to be his greatest supporter, even becoming his assistant in mind-reading performances. They remained deeply in love all their lives but had no children.

During the early lean days, Houdini offered to sell his conjuring tricks to newspapers, but no one was interested. He and Bess resorted to holding “psychic” Demonstrations, in which local tipsters provided them with enough information to impress the audience. The crowd’s eager acceptance of their mediumship, which both knew to be a trick, scared the Houdinis.

By 1900, Houdini had escaped from handcuffs in a Chicago prison and even had broken free of handcuffs at Scotland Yard. His notoriety gained him more lucrative engagements, and his career soared. For the next 26 years, Houdini performed some of the most spectacular feats ever witnessed: escaping from fetters in icy cold water; emerging in minutes from boxes, coffins, kegs, mailbags, safes and gigantic paper bags; hanging from ropes off the ledges of tall buildings, then freeing himself; even coming back to life after being buried alive. There were no rope knots or contraptions that could hold him.

Throughout his life, Houdini was a devoted son to his mother, sending her part of his earnings and remaining in constant touch. After her death, he searched desperately for a way to reach her. He contacted medium after medium with no success. After each failure he would stand over his mother’s grave and say that he’d heard nothing yet. He wanted passionately to believe in Spiritualism, yet was convinced that the movement was nothing more than conjuring tricks.

In 1920, during a tour of England, Houdini and Bess met Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and his family. The two struck up a friendship and an active correspondence. Both had an interest in spiritualism, but from opposite sides, as Doyle was as ardent a believer as Houdini was a skeptic.

During the Doyles’ first American lecture tour on Spiritualism, the Houdinis joined them for a vacation in Atlantic City in June 1922. On the afternoon of June 17, Doyle reported that his wife, an “inspired” (automatic) writer, felt she could get Houdini through to his mother. Bess was asked not to attend to prevent diluting the spiritual force. Bess had told Lady Doyle all about Houdini’s mother the night before, and she cued her husband in their mind-reading code language that Lady Doyle was so informed.

Nevertheless, Houdini determined to be as openminded and religious about the experience as possible. He wrote that he wanted to believe and emptied his mind of all skepticism. For Houdini, June 17 was a holy day, as it had been his mother’s birthday.

Presently, Lady Doyle was seized by the spirit and began shaking convulsively. She asked the spirit if it believed in God, and receiving affirmative raps, made a cross at the top of the paper and began writing furiously. The message was an emotional outpouring of love for Mrs. Weiss’s “darling boy,” describing her happiness on the Other Side and joy that the Doyles had enabled her to finally get through to him. When Houdini asked if his mother’s spirit could read his mind, she claimed that she could, and thanked the Doyles for helping her pierce the spiritual veil. She asked God’s blessing, and then departed.

When Lady Doyle came out of trance, Houdini asked Sir Arthur if he, or anyone, could try Automatic Writing. Urged to try, Houdini picked up a pencil and wrote “Powell.” Sir Arthur was dumbfounded, asserting that Houdini had been contacted by the spirit of his recently deceased friend Dr. Ellis Powell. Doyle claimed that Houdini was profoundly moved by the whole Séance.

Within six months, however, Houdini publicly renounced the communication, finding it a noble try but again a failure. In the first place, his mother was Jewish and would not have started her message with a cross. Doyle countered that Lady Doyle always placed such a holy symbol on her manuscripts to guard against evil influence. Secondly, Mrs. Weiss spoke only broken English and could not write the language at all. Again Doyle had a ready answer, saying that a good medium in trance can receive a message in another language and try to translate them into her own; it was the inspiration, not the tongue, that was important. Lastly, the message did not mention his mother’s birthday at all, and Houdini believed that if the communication were truly from his mother she would have commented on that fact.

As for the Powell reference, Houdini refused to believe he had heard from Doyle’s friend, noting that he and Bess had recently been talking about their magician friend Frederick Powell, whose wife and assistant was ill. That the two should have the same last name was mere coincidence. Doyle disagreed, saying another medium had revealed in a Séance later on June 17 that Powell had tried to reach him and apologized for his abruptness.

The Doyles were angry and hurt by Houdini’s refusal to believe. Although Doyle and Houdini tried to remain friends after that, speaking of anything but spiritualism, the rift could not be repaired. By 1924, they were antagonists.

In January 1923, Scientific American magazine offered $2,500 to the first person who could produce a spirit photograph under test conditions and another $2,500 to anyone who could produce physical paranormal phenomena and have it recorded by Scientific instruments. The magazine’s test committee was composed of William McDougall, Harvard professor of psychology; Daniel F. Comstock, formerly of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology; Walter Franklin Prince, head of the American Society for Psychical Research (ASPR); Hereward Carrington, a psychic investigator; Malcolm Bird, assistant editor of Scientific American; and Houdini.

The committee’s first assignment was the medium Mina Stinson Crandon of Boston, alias Margery. Her enthusiastic husband had written Doyle about his wife’s talents, and Doyle recommended her to the committee without ever meeting her. They began their investigation in November 1923, and Bird prepared a glowing endorsement of her for the July 1924 issue. Unfortunately, the committee had acted without Houdini, who learned of their activities from press clippings while he was on tour. Furious, he arrived in Boston in July to see Margery for himself.

The Crandons suspected Houdini from the beginning and were uncooperative. He, in turn, resorted to trickery to discredit her. For the first Séance, Houdini wore a tight bandage around his upper calf for hours before the sitting, making his leg extraordinarily sensitive. Margery’s spirit Control, her brother Walter, was accustomed to ringing bells during the Séance, and Houdini asked that the bell box be placed between his feet. Sitting on Margery’s left, Houdini claimed his tender leg detected Margery’s almost imperceptible movements to work the box with her left foot.

Houdini caught Margery in several other tricks: throwing a megaphone with her head as if it had fl own by spirit intervention, lifting a table with her head, and again sliding her foot. He waited to expose her, however, until more tests could be conducted. The press claimed Margery had stumped Houdini, further antagonizing him against the Crandons.

Houdini vowed to outwit Margery. In August, he arrived in Boston with a special box for Margery to sit in during the Séances. The box enclosed her body completely, except for her head, neck and arms, allowing little movement of her legs and feet. Margery objected to the cage, stating that such pressure showed little regard for the psychic process. But it did not hamper her performance, as the lid was ripped off, ostensibly by Walter.

The next night Houdini replaced the lid and added locks. The Crandons examined the box and found it satisfactory. Bird burst into the Séance demanding to know why he had been excluded, and Houdini accused him of betraying the committee’s investigation. After he left, Houdini repeatedly reminded Prince to hold Margery’s right hand. Irritated, Margery asked why he kept saying that, and Houdini replied that if her hands were held she could not manipulate anything she might have hidden in the box during the earlier examination.

Soon thereafter, Walter accused Houdini of leaving some articles in the box. Houdini denied this, but Walter explained that Houdini’s assistant had placed a folding ruler in the box which, when found, would be seen as a reaching tool for Margery’s use. Walter screamed out that Houdini was a son of a bitch, should go to hell, and that if he didn’t leave the Crandons, he, Walter, would not return. Many years later Houdini’s assistant admitted his own complicity, saying that Houdini was bent on discrediting Margery.

Doyle and other spiritualists attacked Houdini for his ungentlemanly actions; Doyle even called his former friend a bounder and a cad. Complicating the whole affair was Doyle’s insistence that Houdini himself was probably the greatest medium of modern times. Doyle refused to believe that Houdini could perform his amazing escapes without first dematerializing and then reappearing, and others shared Doyle’s opinion. All of this put Houdini the medium-baiter in the embarrassing position of demurring without really revealing the secrets of his act.

Actually, Houdini believed that if anyone could escape from the Other Side to the physical realm, it was he. Before his death, he and Bess worked out a code using their mind-reading secrets that would tell her that he had succeeded in coming back. (See also Smith Susy.)

On October 22, 1926, a student visiting Houdini backstage in Montreal took him unawares and punched him in the stomach to test Houdini’s claim of extraordinarily firm muscles. The blow was too hard, however, and Houdini died of peritonitis from a ruptured appendix nine days later, on Halloween. No autopsy was performed. Supporters of Houdini suspected the attack was actually murder planned by spiritualists who resented Houdini’s activities, but the suspicions remained unproved. In 2007, his great-nephew, George Hardeen, sought to have his body exhumed for signs of poisoning.

Mediums claiming communications from Houdini besieged Bess Houdini immediately. Lonely and in poor health, Bess fell down a set of stairs on New Year’s Day 1929, calling out to Harry for help. A week later, Arthur Ford, pastor of the First Spiritualist Church of New York, delivered a message purportedly from Mrs. Weiss containing the word “forgive,” a word Houdini had vainly sought. Bess contacted Ford for a Séance.

On January 8, 1929, Bess and several friends sat with Ford, who entered a trance immediately. First his control, Fletcher, spoke, then Houdini allegedly took over, saying, “Rosabelle, answer, tell, pray, answer, look, tell, answer, answer, tell.” The communication sounded incoherent, until Bess removed her wedding band, in which were inscribed some of the words of a song she had sung on stage with Houdini in the early days: “Rosabelle, sweet Rosabelle, I love you more than I can tell. Over me you cast a spell, I love you my sweet Rosabelle.” After singing the song, Bess fainted.

When she revived, Fletcher the control explained the message as a coded communication dating back to the couple’s mind-reading days; decoded it meant “Rosabelle, believe.” Bess promptly confirmed that the message was indeed the secret password. She signed a statement affirming its legitimacy and even wrote columnist Walter Winchell about the affair. Spiritualists rejoiced that Houdini, who had never believed, confirmed the truth of the movement after death.

Within a few years, however, Bess retracted her statements after hearing from radio mentalist Joseph Dunninger that he had read Houdini’s code word in a 1927 biography. She condemned the Ford Séance, attacked all mediums as charlatans and planned to make a movie exposing their trickery, but never did. Bess continued to hold Séances on Halloween for a few years, trying to reach Houdini, but he was silent. In resignation, Bess told her friends that when she died, she would not try to come back.

As Houdini himself once said, anyone can talk to the dead, but the dead do not answer.

SEE ALSO:

FURTHER READING:

- Brandon, Ruth. The Spiritualists. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1983.

- Cannell, J. C. The Secrets of Houdini. New York: Bell Publishing Co., 1989.

- Doyle, Sir Arthur Conan. The Edge of the Unknown. New York: Berkley Medallion Books, 1968. First published by G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1930.

- Houdini, Harry. Houdini: A Magician Among the Spirits. New York: Arno Press, 1972.

- Somerlott, Robert. “Here, Mr. Splitfoot”: An Informal Exploration into Modern Occultism. New York: The Viking Press, 1971.

SOURCE:

The Encyclopedia of Ghosts and Spirits– Written by Rosemary Ellen Guiley – September 1, 2007