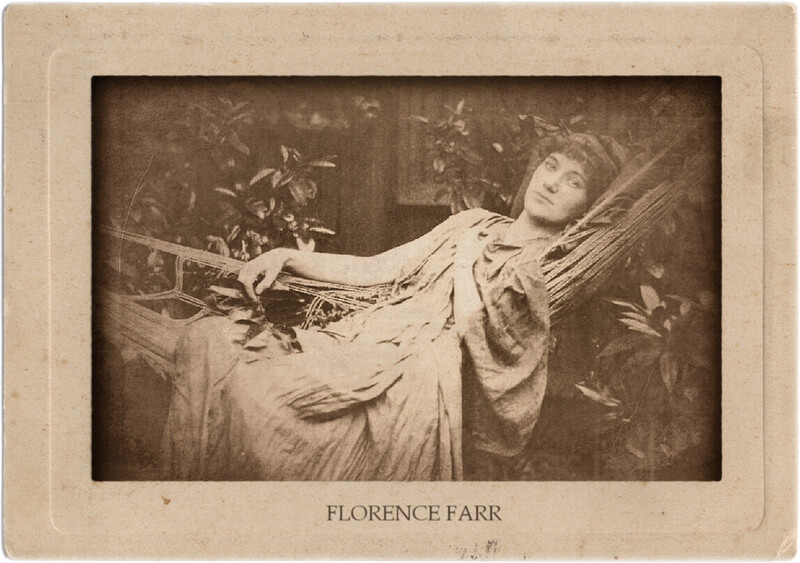

Farr, Florence Beatrice

Florence Beatrice Farr (1860–1917) was an English actress, occultist, and an important member of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. Florence Farr was born on July 7, 1860. Her father was a physician and named her after his friend, the famous nurse Florence Nightingale.

According to Farr’s horoscope, her sun was in the 12th house, which presaged psychic abilities and an interest in the occult. Both proved to be true. In her teens, Farr became friends with the daughter of Jane Morris, May Morris, who served as a model in preRaphaelite paintings. Farr and May Morris modelled for “The Golden Stairs,” painted by Sir Edward Burne-Jones. Farr was intelligent and gifted with a beautiful voice. She was not content with the traditional role expected of Victorian women—to marry and have children and be obedient to a husband.

She attended Queen’s College, the first woman’s college in England. After college she taught, but the job failed to hold her interest. She turned to acting and was modestly successful. She fell in love with an actor, Edward Emery, and married him, but after marriage he treated her like a possession and demanded that she stay home and fulfill her traditional domestic duties. Farr rebelled, and a few years later they separated. Emery went to America.

Farr never remarried, though she had numerous lovers. In 1890 Farr moved in with her sister in Bedford Park, London, and the two entered a bohemian subculture of artists, political radicals, and free thinkers. Here she felt at home, on an equal footing with men.

Her stage performances as a high priestess drew the admiration of George Bernard Shaw and William Butler Yeats, both of whom envisioned her as the perfect woman to perform in their plays. Both men wrote plays entirely for her: Yeats did The Countess Cathleen, and Shaw did Arms and the Man. With the help of the wealthy Annie Horniman, Farr helped Yeats and Shaw have their plays produced.

Also in 1890 Farr joined the Golden Dawn, taking the magical motto Sapientia Sapienti Dono Data, “Wisdom is a gift to be given to the wise.” Shaw was dismayed, believing occultism to be far beneath her talents. But Farr treated her magical career quite seriously, seeking to transform her very body into an instrument for the receipt of divine wisdom. She was determined to be dominated by no man ever again, not even the adoring Shaw and Yeats.

She advanced quickly through the grades and was initiated as Adeptus Minor in 1891, the second person to achieve the rank. In 1892 she became Praemonstratrix (leader of the order) and worked to improve the Golden Dawn’s rituals.

Her skill as an actress lent her a commanding presence in the performance of ceremonial magic. Farr became skilled in enochian magic and divination with the I Ching. She was particularly skilled in scrying. She contacted the spirit of an Egyptian priestess of the Temple of Amon-at-Thebes, Nem Kheft Ka. The authenticity of the contact was validated by Samuel Liddell Macgregor Mathers, one of the three founding Chiefs of the Golden Dawn.

Mathers encouraged Farr to learn the temple’s rituals for use in the Golden Dawn. As a result, Farr attempted an evocation of the Spirit Taphthartharath with Allan Bennett and two other members. Farr took the dangerous role of becoming Thoth and then commanding the spirit, rather than using the traditional magical approach of using will and magical tools.

Under Farr’s leadership as Praemonstratrix, the Golden Dawn grew rapidly. She eased the examinations for advancement by eliminating written tests and substituting oral ones. She also made it easier for gifted students to become adepts, as she desired to have them join “The Sphere,” a Second Order group that specialized in scrying.

But rather than benefiting the Golden Dawn, the easing of requirements only served to fuel petty intrigues and jealous bickering, which escalated over time. When William Wynn Westcott resigned as Chief Adept in Anglia in 1897, Farr assumed the position. By then, rifts were widening, and scandals and infighting ensued.

Farr rejected Aleister Crowley for initiation as Adeptus Minor, citing his “sex intemperance” as a major reason. Farr resigned, but Mathers refused to accept it. He revealed to her that Westcott had forged letters pertaining to an alleged lineage of occult tradition for the Golden Dawn, which Farr made public to members.

After Crowley made his famous but failed attempt to storm the London temple, Mathers was expelled, and the Golden Dawn reformed initiation for Adeptus Minor, enabling candidates to bypass the entire Outer Order. By that time, the Golden Dawn was riddled with rifts and factions.

Farr, exhausted by them all, broke all connection with the Golden Dawn in 1902. She returned to her acting career and co-wrote and produced two plays about Egyptian mysteries. In 1907 she toured America, but by 1912 her acting career faded along with her youthfulness and beauty.

She took a teaching job in Ceylon and became a Buddhist nun. A few years later she developed breast cancer and had a mastectomy. She wrote to Yeats about it, and he knew she was near her end. Two months after sending the letter, Farr died alone in a hospital in Colombo on April 29, 1917. Her body was cremated, and her ashes were scattered in a river.

Throughout her magical life, Farr was a prolific writer, authoring numerous articles on occultism as well as two novels based on her own experiences. She was especially interested in alchemy and Egyptian magic and wrote on the parallels between Egyptian magic, alchemy, Hermetic, Kabbalistic, and Rosicrucian thought.

For the Golden Dawn, she wrote “flying scrolls”—study materials for the Second Order—on astral travel and Hermetic love and higher magic.

FURTHER READING:

- “Florence Beatrice Farr.” Available online. URL: https://www. golden-dawn.org/bioffarr.html. Downloaded June 29, 2005.

- Greer, Mary K. Women of the Golden Dawn: Rebels and Priestesses. Rochester, Vt.: Inner Traditions, 1995.

SOURCE:

The Encyclopedia of Magic and Alchemy Written by Rosemary Ellen Guiley Copyright © 2006 by Visionary Living, Inc.