Urbain Grandier

Urbain Grandier (d. 1634) was a priest framed and executed in the Loudun Possessions of Ursuline nuns in France. Urbain Grandier was brought down by his own arrogant charm and success, Reformation politics, and a spiteful nun he spurned. Burned alive at the stake, he was the only person to be executed in the case. Grandier, son of a lawyer and nephew of Canon Grandier of Saintes, was born to a life of privilege. A bright and eloquent student, he was sent at age 14 to the Jesuit College of Bordeaux. He spent more than 10 years studying there and took his ordination as a Jesuit novice in 1615. A promising career lay ahead of him.

Grandier’s Troubled Rise

At age 27, Grandier had accumulated many influential benefactors and was appointed curé, or parson, at Loudun. He also was made a canon of the collegial church of the Holy Cross. The town was sharply divided between the Protestant Huguenots, who abhorred the church, and Catholics.

Town opinions immediately were divided over Grandier. Women found him appealing and a significant improvement over his aged predecessor. Grandier was young, handsome, sophisticated, and interesting. He was given immediate entree into the highest social circles. He was flattering.

In times past, clerics could get away with quiet sexual escapades and affairs. But in the atmosphere at Loudun, disapproval of scandalous behavior was increasing. Grandier, a wayward priest, should have paid heed to the social climate, but instead he felt entitled to enjoy women, single and married, an attitude that earned him simmering animosity among Loudun’s menfolk.

Professionally, he excelled in preaching and in performing his religious duties, which earned him resentment among his peers. He was able to stay out of trouble because he had the support and favour of the town’s governor, Jean d’Armagnac.

Grandier, thinking himself to be invulnerable, made arrogant mistakes. He became embroiled in quarrels and did not hesitate to criticize the behavior of others, especially the Carmelites and Capuchins. He disparaged their relics, a source of income, and caused them a loss of patronage.

One of Grandier’s many amorous affairs was with Philippe Trincant, the daughter of Louis Trincant, the public prosecutor of Loudun, who was one of Grandier’s staunchest allies. That Grandier, who had his choice of women, jeopardized his relationship with the prosecutor in such an unforgivable way reveals his arrogance. Philippe became pregnant and Grandier abandoned her, creating another great enemy in Louis Trincant. The prosecutor led an informal but growing group of citizens who wished to bring Grandier down for one reason or another.

Grandier then set his sights on Madeleine de Brou, 30, the unmarried daughter of René de Brou, a wealthy nobleman. Madeleine had turned away many suitors, preferring a pious life. Unexpectedly, Grandier actually fell in love with her. He persuaded her to marry him, angering her family and Pierre Menuau, the advocate of King Louis XIII, who had been trying to win Madeleine’s hand for years. Grandier’s enemies complained to the bishop, HenryLouis Chasteignier de la Rochepozay, who lived outside Paris, that Grandier was out of control. He was debauching married women and young girls in his precinct, was profane and impious, and did not read his breviary, among other crimes. The bishop, who despised Grandier, ordered him to be arrested and imprisoned. The case was adjourned, however, and Grandier was given time to clear himself with his superiors.

Instead, accusations of his impropriety were heaped upon him as townspeople came forward. He was accused of having sex with women on the floor of his own church. He touched women when talking to them. Grandier decided to appear voluntarily before the bishop rather than be humiliated by arrest. He was arrested anyway and taken to jail on November 15, 1629.

After two weeks in the cold and dank prison, Grandier petitioned the bishop for his release, claiming he had repented. The bishop’s response was to increase his punishment. On January 3, 1630, Grandier was sentenced to fast on bread and water every Friday for three months and was forbidden to perform sacerdotal functions forever in Loudun and for five years in the Diocese of Poitiers. Such a sentence spelled ruin for Grandier, and he announced his intention to appeal the case. He had good odds of winning, for the archbishop was a close friend of Grandier’s key supporter, Governor d’Armagnac.

Grandier’s enemies appealed to the Parlement of Paris, claiming he should be tried by the nonsecular court. A trial date was set for August. Only six years earlier, a person had been burned alive at the stake for committing adultery. Grandier’s enemies hoped he would have the same fate. The case went in Grandier’s favour. Accusations from the townspeople were recanted, and Philippe’s father decided to protect what little remained of his daughter’s reputation by keeping silent about her illegitimate child fathered by Grandier. The archbishop remained supportive of Grandier.

Grandier was reinstated as curé, and he must have thought himself to be invulnerable. Friends advised him to be smart and leave Loudun, but he refused, perhaps to spite his enemies.

Grandier’s Downfall

The event that sealed Grandier’s doom at first seemed trivial. JEANNE DES ANGES, the mother superior of the Ursuline convent at Loudun, invited him to take the vacant post of canon. He declined, citing the press of too many other duties. He had never met Jeanne or been to the convent. Unbeknowst to him, Jeanne was harboring a secret sexual obsession with him, and he had been the object of salacious gossip among the nuns for some time. Jeanne, a mean and vindictive woman, was stung. The man she appointed to fill the post, Canon Mignon, disliked Grandier. He became privy to the sexual secrets of the nuns, their nervous temperaments, and their ghost pranks in their haunted convent. It was soon easy to let them run out of control and become bewitched and beset by Demons. Mignon conspired with Grandier’s enemies to let it be known that he was responsible for their afflictions. Grandier shrugged off these stories, confident no one would believe them. As fantastic as they were, the stories found an audience not only among his enemies, but in the fertile political territory of Catholics and Protestants trying to sway the faithful with Demonstrations of their spiritual firepower. Nothing played better for the Catholics than Demonic possession.

Soon the nuns were giving hysterical performances for swelling crowds, under the exorcisms of Mignon and a Franciscan, FATHER GABRIEL LACTANCE, and a Capuchin, Father Tranquille. Both Lactance and Tranquille were believers in the Demonic.

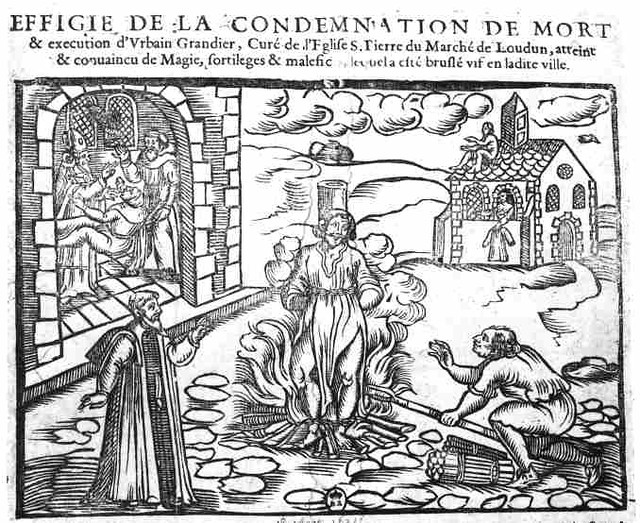

Torture and Death

On August 18, Grandier was convicted and sentenced to be tortured and burned alive at the stake, and his ashes scattered to the winds. The sentence also stated that he would be forced to kneel at St. Peter’s Church and the Ursuline convent and ask for forgiveness. A commemorative plaque would be placed in the Ursuline convent at a cost of 150 livres, to be paid for out of Grandier’s confiscated estate. The sentence was to be carried out immediately. Grandier made an eloquent speech of his innocence to the stone-faced judges. So moved were the spectators, however, that many burst into tears, forcing the judges to clear the room. Grandier refused the last services of Lactance and Tranquille and made his final prayers. The exorcists, pushing Grandier’s alleged guilt to the maximum, insisted that when he said the word God he really meant “Satan.”

In anticipation of a guilty verdict and execution, about 30,000 people had flocked to Loudun to witness the spectacle.

Grandier’s body was shaved, but his fingernails were not ripped out because the surgeon refused to obey the court. In the interests of moving matters along, that punishment was forgone. He was then prepared for the question extraordinaire, the confession of his crimes. Lactance and Tranquille exorcized the ropes, boards, and mallets of torture, lest the Demons interfere and relieve Grandier’s suffering. The curé was bound, stretched out on the floor, and tied from his knees to his feet to four oak boards. The outer boards were fixed and the inner boards were movable. Wedges were driven between the pairs so that his legs were crushed. The excruciating crushing took about 45 minutes. At every blow, Grandier was asked to confess, and he refused. The final hammer blows were delivered by Lactance and Tranquille. Grandier’s smashed legs were poked, inducing more pain. The exorcists declared that the Devil had rendered him insensible to pain. For two more hours, Grandier was cajoled to sign the confession prepared for him, but he steadfastly refused, saying it was morally impossible for him to do so. The court finally gave up and sent him off to the stake. Grandier was dressed in a shirt soaked in sulfur and a rope was tied around his neck. He was seated in a muledrawn cart and hauled through the streets, with a procession of the judges behind him. At the door of St. Peter’s Church, the procession halted and a two-pound candle was placed in Grandier’s hands. He was lifted down and urged to beg pardon for his crimes. Grandier could not kneel because of his crushed legs and fell on his face. He was lifted up and held by one of his supporters, Father Grillau, who prayed for him as both of them wept in a piteous scene. The onlookers were ordered not to pray for Grandier, for they would be committing a sin. At the Ursuline convent, the same procedure was repeated, and Grandier was asked to pardon Jeanne and all the nuns. He said he had never done them any harm and could only pray that God would forgive them for what they had done.

Father René Bernier, who had testified against Grandier, came forward to ask for Grandier’s forgiveness and offered to say a mass for him.

The place of execution was the Place Saint-Croix, which was jammed with spectators. Everyone who had a window had rented it out to capacity. More spectators sat on the church’s roof. Guards had to fight a way through the throng to reach the 15-foot stake driven into the ground near the north wall of the church. Faggots were piled at the base of the stake.

Grandier was tied to a small iron seat fastened to the stake, facing the grandstand, where his enemies drank wine in celebration. He had been promised strangulation by the noose around his neck prior to the start of the fire. The Capuchin friars exorcized the site, including the wood, straw, and coals that would start the blaze and the earth, the air, the victim, the executioners, and the spectators. The exorcisms were done again to prevent the interference of Demons to mitigate Grandier’s suffering and pain. His death was to be as excruciating as possible. Grandier made several attempts to speak, but the friars silenced him with douses of holy water and blows to his mouth with an iron crucifix. Lactance still demanded a confession, but Grandier gave none. He asked Lactance for the “kiss of peace,” customarily granted to the condemned. At first, Lactance refused, but the crowd protested, and so he angrily complied, kissing Grandier’s cheek. Grandier said he would soon meet the judgment of God, and so, eventually, would Lactance. At that, Lactance lit the fire, followed by Tranquille and another exorcist, Father Archangel. The executioner moved quickly to strangle Grandier but discovered that the noose had been secretly knotted by the Capuchins so that it could not be tightened. The friars doused some of the flames with holy water to exorcise any remaining Demons. Left to burn alive, Grandier began screaming.

A large black fly appeared, which the exorcists took as a sign of Beelzebub, the Lord of the Flies. Grandier’s body was consumed in flames. Then a flock of pigeons appeared, wheeling around the fire. Grandier’s enemies took this as a sign of Demons, and his supporters took it as a sign of the Holy Ghost.

When the fire burned itself out, the executioner shoveled the ashes to the four cardinal points. Then the crowd surged forward to scavenge grisly souvenirs of teeth, bits of bone, and handfuls of ashes, to be used in Charms and spells. The relics of a sorcerer were considered to be quite powerful. When all were gone, the satisfied crowd dispersed to eat and drink.

Later, back at the Ursuline convent, Jeanne was exorcized again. She said the fly was the Demon Baruch, who had been intent on trying to throw the priests’ exorcism book into the fire. She confirmed that Grandier really had prayed to Satan, not to God. She said he suffered an excruciating death thanks to the exorcisms of the priests, and that he was suffering special torments in Hell. Jeanne and the other nuns were remorseful about Grandier and worried that they had sinned. Soon, however, the priest was forgotten, as the possessions and exorcisms continued. Tranquille and Lactance suffered Demonic problems themselves and died.

SEE ALSO:

FURTHER READING:

- Certeau, Michel de. The Possession at Loudun. Translated by Michael B. Smith. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000.

- Ferber, Sarah. Demonic Possession and Exorcism in Early Modern France. London: Routledge, 2004.

- Huxley, Aldous. The Devils of Loudun. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1952.

SOURCE:

The Encyclopedia of Demons and Demonology – Written by Rosemary Ellen Guiley – Copyright © 2009 by Visionary Living, Inc.